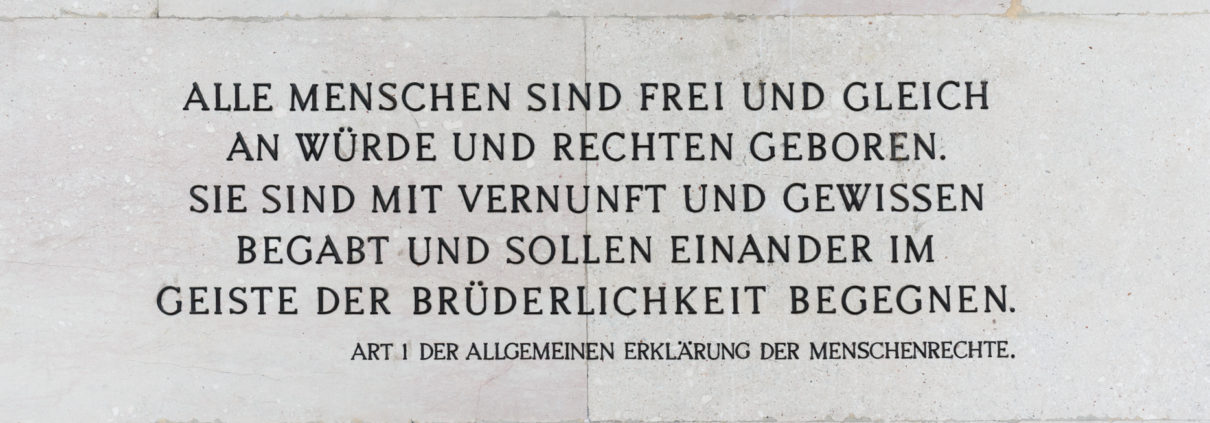

EQUALITY OF RIGHTS

All human beings are born free and

equal in dignity and rights.

They are endowed with reason and conscience

and should act towards one another

in a spirit of brotherhood.

A constitution is a response to what individuals have undergone and experienced. The constitution is to provide the basis for peaceful coexistence, because people have experienced insecurity, violence, war and their disastrous consequences. The constitution is to guarantee freedom because people have experienced the destructive nature of a life lived in fear. The constitution is to guarantee that all individuals are treated as equals because people have experienced (and still experience) the devastating effects that oppression and social exclusion can have.

For a constitution to fulfil these functions, it must be more than a collection of promises and nice ideas. A constitution must establish rights and must guarantee that these rights are enforceable.

What is „the law“?

When the term „law“ is used in a general context, what is meant are usually legislation and legal rules. They regulate which conduct is required in particular situations, such as in road traffic. They define the procedure for establishing a business enterprise. They determine what are the consequences if one individual causes bodily injury to another. They specify what are the tasks to be performed by police, administration and the courts of law.

What does it mean to have „a right“?

When we say that „somebody has a right“, we mean that an individual may assert particular claims against other individuals (or against the state). He or she may demand that somebody performs an act or desists from doing so. Rights differ from other claims (such as a wish or a request) in multiple regards:

- They are laid down formally (e.g. in the constitution or in statutory law),

- They must be invoked in some form,

- There always exists some sort of relationship to the state,

- If a claim is lawful – that is to say, a „right“ -, it can be enforced.

Rights must be enforceable

Whenever we are talking of a right – i.e. a lawful claim -, what is essential to make it a right is its enforcability. This means that other individuals or the state must accept that somebody is entitled to something, that something „is due to him or her“. If this claim is not fulfilled voluntarily, it can in many cases be enforced „by means of coercion“. This may happen by seizing his/her salary or by sentencing him/her to imprisonment. What is important in any of these cases: Rights cannot be enforced against others „just somehow“. Enforcement is always subject to a specific procedure, and coercion is permitted only if ordered by a court of law or by an administrative authority (see the text on Crime and Punishment). Nobody may take another person’s property or money because he considers himself to have a right to it. Nobody may inflict violence on or detain another person because he thinks he has a right to. Not the principle „Might makes right“ should prevail – i.e. not superior strength should be free to enforce its will -, but rights are to be decided on by trained judges in fair proceedings.

Rights and relationships

A legal system and the rights enshrined in it always regulate relationships between individuals. This also applies when somebody claims his right „to a certain thing“ – such as a house -: He does not enter into court proceedings against the house but asserts his right against other individuals.

The legal system and the rights which somebody has are to provide guidance and certainty when individuals deal with one another. They regulate how we are to deal with one another. They are to ensure that we can rely on each other even when we are dealing with strangers.

If somebody invokes his or her right, this may mean that there are troubles in his/her dealings with another individual. It may mean that it is not clear which rules must be followed. It may mean that the other’s rights are denied. In any case the relationship is not running smoothly. Someone denies something to another, a dispute arises, whose settlement fails. Many people therefore tend to be sceptical when somebody claims „his right“. They surmise that he or she just seeks to carry his point, is incapable of giving way or is picking a quarrel. In Austria, a phrase sometimes used in such situations is: „Wir werden schon keinen Richter brauchen!“, literally: „We won’t need a judge.“ This means that no outsider shall intervene in our affairs.

It also occurs that people invoke their „right“ or go to court to intimidate others. Even then, however, it’s not the law that sows the seeds of discord. What comes first are conflicts, quarrel or the feeling of suffering injustice. Rights then are a means to make such conflicts visible. Legal proceedings (e.g. before court) can make it possible to resolve the dispute in some way and to reach a decision.

The right to have rights

To have rights means to be a member of a legal community, to be respected, and to be free to live (as far as possible) a self-determined life. In a modern state, law is the basis for coexistence in a society. It regulates the relations between all individuals living there (see the text What is the Constitution). Whoever has rights can participate in that society. We say that somebody is recognized as a „subject of the law“. A human being that has no rights remains excluded in multiple respects. The philosopher Hannah Arendt, who herself had a long experience as a refugee and „stateless person“, therefore said that the foremost human right is the right to have rights. In Austria, the following provision has been in force since 1811: „Every individual has inherent rights, already evident from common sense, and has thus to be considered as a person.“ (§ 16 Austrian Civil Code)

Equal rights

Equality of rights means that all individuals have rights – no matter whether they are male or female, children or adults, physically or mentally handicapped, and irrespective of their origin, their religion, their colour or their sexual orientation. We say that law safeguards the dignity of each individual. Nobody is to be discriminated against (i.e. treated differently or worse) solely on the basis of certain characteristics.

Equality of rights does not prohibit to differentiate between individuals. Rather, equality of rights ensures that individuals – their diversity notwithstanding – have equal rights and may freely develop. Nor does equality of rights preclude that the law may differentiate between different individuals or groups of individuals. However, such differentiation is only permitted if it can be justified by specific factual reasons. In assessing such matters, it is always necessary to also question one’s own position. Furthermore, one has to bear in mind the question by which standards (or against which background) somebody or something is perceived as equal or unequal. To ensure equality of rights, in may in certain cases also be necessary to provide particular support to certain individuals or groups of individuals.

Modern democratic states under the rule of law (see the text on The State under the Rule of Law) are based on the fact that each individual has equal rights. This is not a matter of course, as is illustrated by the term „equality of rights“. When we talk about „equal rights“, we assume that these rights already exist, whereas the term „equality of rights“ also implies a commitment, a need and a process of creating actual equality of rights.

What matters is the status as an individual

Each person has equal rights. When we talk about equality of rights, what we have in mind is the person as an individual. This does not mean that family and relatives, religious communities or other groups to which persons belong are unimportant. Nobody lives for himself/herself alone, and relations to fellow human beings are essential for the life of each individual and for life in a society.

The fact that each person has rights means, however, that each person has the right to be treated as an individual and that his or her claims, but also any charges that may be brought against him or her, are carefully examined and investigated. The fact that each individual has rights means that he or she may claim these rights – no matter what his or her family, or any other community, may think about it.

The long way to equality of rights

That all individuals have rights and that they can participate as equals in social and economic life was for a long time unimaginable. Even today it is still denied by many people and in many states of the world. In their view, certain characteristics that distinguish individuals (sex, colour, origin, religion) should also be decisive for an individual’s status in state and society. Depending on the characteristics an individual has, he or she is to have or not have particular rights. Until this day citizenship is a criterion that determines which rights an individual is to enjoy (see the text on the Republic).

Throughout many centuries, an order of society as described above was a matter of course in Europe. Some individuals had more rights than others – no one but them could, for instance, own land or hold state offices. Numerous individuals had no rights at all. Such distinction between individuals is particularly striking because one central message of the Christian faith (to which the overwhelming majority of the population adhered) is that each human being is made in the image of God. According to the Christian doctrine, God encounters man in each of his fellow individuals, for which reason Christians might well be expected not to subscribe to any distinctions based on origin, status or property.

In the Fifteenth century scholars began to reflect on these differences from a new perspective. However, they read not only the Bible but also the works of ancient philosophers who had reflected on mankind and on what it means to live a good life. We call these scholars „humanists“ (from Latin „homo“ = man, mankind, human). Their thoughts marked the beginning of a long development which led to the so-called „Enlightenment“. During that age, the old order with its manifold inequalities, and in which the multitude of individuals were denied any rights, also came to be challenged. Many philosophers and writers sought to justify the equality and freedom of all humans from a general (i.e. not solely religious) point of view. It was at first in North America, in what is today the United States, and then in France that it was laid down in the Eighteenth century that all humans are to be free and have equal rights. Freedom and equality were, at that stage, no longer based on religious demands, but were provided by a man-made constitution and by law. Since then, many individuals have been committed to formulating equality and dignity as universal – i.e. worldwide – principles and to raising awareness of them in all religions and cultures.

Advances and setbacks

This does not mean, however, that equality of rights became a reality in these countries immediately. Even though the commitment did exist, equality of rights was initially granted only to certain males. In the USA it was to take another several decades before slavery was abolished. In many countries it took a long time until adherents to a religion other than that of the majority were granted full rights in social and economic matters (e.g. Jewesses and Jews). Similarly difficult and lengthy discussions took place before women could enjoy the same rights as men. In Switzerland women got the right to vote only in 1971 (in some parts of Switzerland it even took until 1990). In Austria, husbands could determine until 1977 whether or not their wives were permitted to work in a job. Until this day, homosexuals are fighting also in Austria for an equal right to marriage.

Over time, equality of rights has been called in question on repeated occasions, and it still is. And as European history in the 20th century shows, it may be a very short way for humans to be deprived of their rights on gounds of certain characteristics. When the National Socialists rose to power in Germany in 1933, it had for years been a matter of fact that Jews but also political dissenters were designated in political discourse as „parasites“ („Schädlinge“). Now they were also denied basic rights, initially in business life and then progressively in other spheres. This was followed by persecution, expulsion and annihilation. These developments were not limited to Germany but occurred in many parts of Europe.

It was due to these experiences that after World War II and the end of Nazi rule, human rights were to be protected internationally. The United Nations proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (see the text on Austria in a Global Context). In Europe, the European Convention on Human Rights was adopted (see the text on Austria in a Global Context) and the European Court of Human Rights established (see the text on Austria in a Global Context). They ensure that each individual has equal rights and can enforce these rights even if they are denied to him/her in his/her home state.

The commemoration of the holocaust, the annihilation of almost 6 million Jews, and the persecution and killing of political dissenters, the disabled, homosexuals, Roma and Sinti, confessing Christians and Jehova’s Witnesses serves not only the remembrance of the victims. It is not only a warning calling to mind the abysmal dimension of evil man is capable of. It also brings to memory that each individual is equal in dignity and in rights, and that we all are called upon to stand up against whoever contests these rights.

Not only in the law

Experience in history shows that it is not sufficient that individuals are recognized as equal „only in the law“. For law and legislation to be effective, there must be institutions which publicize them, claim their respect and enforce them. What is needed above all is individuals who are committed to them and who – in their everyday lives, in their families, at school and at work – recognize all others as equal in rights. What is needed is individuals who, in a sensitive and respectful manner, react to developments through which others – in an open, covert or simply inconsiderate manner – are denigrated or degraded. Such sensitivity and awareness is necessary in everyday life and in an overall context – for instance when financial and social inequality in a society becomes so flagrant that it jeopardizes democracy and the state under the rule of law, or when people meet with ill will and hostility because they had to flee from their home countries and are foreigners.

Alexis de Tocqueville, a French scholar, wrote as early as in 1840 that there are only two ways to create equality of rights: by according rights either to each citizen or to none. He advocated equal rights at a time when traditional religion and common morals were about to undergo rapid change. He therefore considered it of primary importance „amidst the general unrest“ to link the concepts of rights to personal interest. If that failed, he asked, what would remain with which to rule the world other than fear?